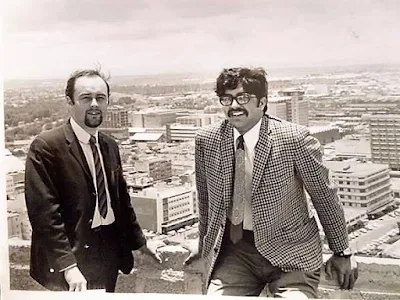

Mike Parry and photographer Azhar Chaudhry

Mike Parry

Life in the Golden Age

BACK in December 1960, when Patrice Lumumba,

first prime minister of the Congo was a few weeks away from ending his short

life, I was about to begin my long career in journalism. The weekend after

finishing my education at the Prince of Wales, now Nairobi School, I was

sitting in the proofreading room of the Daily Nation

and beginning an unexpected education in the finer points of bringing out a

daily newspaper.

The first edition of the Nation

had been printed just a couple of months before when on October 3, 1960 the new

newspaper was born. It was to be my learning ground for the next nine years –

and it could have been longer but for the paper’s reluctance to be fair to its

locally employed staff.

To be honest, journalism was not top of my

mind as a profession as 1960 wound down with exams and the prospect of earning

a living. My best subject was English and when the Nation

put a notice on the school board offering an apprenticeship in newspapers, it

seemed worthwhile to marry the two.

My father would have preferred to send me to

the UK where I could try for a cadetship in newspapers and be trained in the

heart of journalism. I had a good circle of friends in Kenya as well as a

steady girlfriend and I did not want to be parted from them for a country I

had only recently left.

So, from my days of being a carefree schoolboy

with more interest in teenage parties than political parties, I was suddenly

proofreading local and world news in the pokey room where Jack Bottell and his

team operated – all European readers assisted by African copyholders. No summer

holidays for me – just straight into learning about type sizes, galleys,

literals and page proofs as Lumumba was put to death by a makeshift firing

squad watched on by Moise Tshombe.

All local and overseas copy ended up in that

little proofreading room where, it seemed, everyone smoked. Everyone had a

source for cheap NAAFI fags and puffing and proof-reading seemed made for each

other. I rarely saw Mona Blakely without a cigarette on her lips and, up the

curly stairwell to the newsroom, subs and reporters were just as supportive of

the tobacco industry.

An escape was to go and talk and flirt with

the incredibly sexy Laila, the lovely Ismaili who was about my age and, like

me, had just started on the paper. We were good friends and, if it wasn’t for

the social rules of the time, I’d have gladly had her as a girlfriend. Laila

was the sweetest person and deserved more out of life than she got in later

years.

They were exciting times, not just because I was part

of the infectious business of news gathering but because I was one of an

enthusiastic multiracial group all keen on seeing the Daily Nation

succeed against the odds and against the East African Standard, which

had been going since 1905.

Resources were slim – copy from the

established news agencies only ran for a few hours a day at first. The library

– a necessary source of background before an interview – had few cuttings. Even

seating was limited in the newsroom and finding a typewriter – one that worked

smoothly – was almost as difficult as getting the story.

All this was ahead of me because, a year after

joining the Nation, I was called up for National service in the Kenya Regiment. I attended

an appeals panel with Bob Petty, who had some recruitment title, but our

request for a deferment was denied and in January 1962 I found myself in Lanet

with 75 other teenagers being inducted into army life by British NCOs.

When I returned in July, the Nation

was not quite sure what to do with me. They’d promised some form of training

but there was no set structure. African journalists who showed promise were

sent overseas. Locals like myself and Cyprian Fernandes were left to our own

devices.

I was put out of sight in the telex room,

supposedly overseeing the operation and deciding what copy from the agencies

was to be sent on to our branches in Kampala and Dar es Salaam. The main

operator was Joel, very good on the keyboard even when drunk, which was often.

He reluctantly tolerated this young mzungu just as the newspaper tolerated

his frequent pub visits – probably because of his seniority in the print union.

The incessant chat-chat of the telexes had its

excitement – like during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis and, years later, when I

watched as an Associated Press story, bearing my by-line, came back over the

wires.

It was probably Sports Editor Brian Marsden

who gave me an escape from the wire room. He allowed me to write the occasional

sports report and, surreptitiously it seemed, I snuck into the newsroom with

the help of David Barnett, the Aussie News Editor – later to become Malcolm

Fraser’s press secretary – who got me onto the diary.

A word of praise here for Joe Rodrigues, a

friend and quiet mentor, who encouraged my efforts while pointing out my

mistakes. Joe was a great newspaperman, unfairly overlooked on the Nation

because he was not African. He was always fair, well-respected and died far too

young. But I was privileged to have worked with him.

Things seemed to happen quickly in 1963. I was

covering all sorts of stories but not always with enthusiasm. I hated courts

and disliked Parliament. I loved human interest stories, especially those

involving Kenya’s tourism and wildlife industries.

And being first on the scene did not always

guarantee success. Within hours of a reported mutiny and possible coup at Lanet

Barracks – where I trained the previous year – photographer Anil Vidyarthi and

I were racing to the scene, twice being buzzed by British soldiers who

exercised an ambush drill – rifles at the ready - as we passed them on the

road.

Our attempts to turn right to Lanet were

foiled by a roadblock. This is an ongoing emergency, we were told, before being

ordered into Nakuru. Our first report that night was our last. We were barred

from leaving Nakuru and even though we broke out on a backroad the next day, it

was all too late. The coup attempt was over and the slower media, who left

Nairobi long after us, were given an escorted tour of the barracks and beat us

with stories and pictures. We limped back to Nairobi after them, after being

towed for the final section because we had mortally wounded the office car

during our off-road antics.

In 1964, turning 21, I met the love of my life

and got engaged to Valerie, my wife of 53 years. With their usual bad timing,

the Nation then asked me to become the paper’s

correspondent in Uganda in place of Rex Brindle. It would mean living in

Kampala but with the promise of a flight to Nairobi once a month to see my fiancée!

Val and I decided to chance the separation. It

would test our love but also give me a chance to broaden my skills as a

Uganda correspondent. The six months I spent in Kampala gave me a freedom away

from the daily news list and I developed as a columnist and a film reviewer.

Getting out of Uganda was a lot harder. Despite

promises that the posting was only for six months, the Nation

was not rushing to find a replacement. Eventually, I arranged for my visa to

expire and my car vehicle licence to run out and I returned quietly to the

Nairobi newsroom the next Monday morning. I was lucky enough to write the

front-page lead for six straight days on return – something about a big strike,

I think – and deserting my post was never mentioned again.

Like all journalists, I had my share of scoops

and misses on the Nation. We can all list pop stars and princes,

pioneers and prime ministers that we’ve interviewed along with criminals and

comedians. The early hits are in a box of cuttings somewhere. We all wrote thousands

of words at what I believe was the most exciting time in newspapers – the days

of tight deadlines and hot metal, when stories were balanced and written

without a personal slant.

There were no mobile phones to make the job

easy. You had to find a phone that worked when sending in urgent copy.

Dictating a story from scratch was a skill developed on the job. And proof was

always vital.

Such caution seems severe today, but it was

the way things were done back then. We did not publish rumours or gossip and

even diary pages were guarded when it came to tittle-tattle. No stories about

celebrity marriage splits, royal bumps or addictions.

Around 1969, I confronted a bearded Paul

McCartney in the crowded Thorn Tree. He denied – three times! - he was a holidaying

Beatle. By the time I had rung the office again to ask what had happened to the

photographer, McCartney and his mates had disappeared. For days after, both

newspapers staked out local hotels (neither admitting why they were doing so)

in an effort to nail McCartney. The day before leaving Nairobi, a little girl

spotted McCartney at a local swimming pool and asked for his autograph. He

obliged. Her father took this “proof” to the Standard which ran the

story. The Nation missed out.

It was around this time that I left the Nation. By then, I had a regular column on tourism

and wildlife. My stories on poaching were not always well received by members

of the ruling elite and others in government which got me worried about our

future in Kenya with a young family.

Most European journalists were from the United

Kingdom. All were on overseas contracts and every two years enjoyed paid leave

out of Kenya. I was among the few with no such safeguards. When I asked for

some future protection, for the family to be repatriated in an emergency, it

was refused. So, reluctantly, I left to join the Standard.

While I enjoyed overseas leave and

entitlements and greater privileges as a columnist, my switch in papers

probably coincided with a change in the fortunes of both publications, with the

Nation

being more widely accepted by its African readers – which was always the goal

of the paper’s founders. The Nation’s great coverage of Tom Mboya’s assassination, I suggest, was probably a turning point.

I enjoyed four years on the Standard

and not a few scoops – telling the world of plans to turn Ngorongoro over to

agriculture and George Adamson’s graphic description of shooting his beloved

lion Boy were two memorable yarns – before it was time to leave Kenya for

family reasons.

I have worked on half a dozen newspapers in

Durban, Perth and Sydney since those heady days in Nairobi but my time on the Nation

was possibly the most memorable for the time and the place. I worked with some

top people and shared many drinks at the Sans Cheque. I can’t remember all the

names of colleagues and I’d insult those left out. I know many have long gone –

some far too early – so it is good to be in touch with those still around –

like my old mate Skip Fernandes and, of course, my favourite Nation

photographer, Azhar Chaudhry.

Azhar got pissed taking photographs at my 21st

birthday, took the shots to record our 1966 wedding and, I am happy to say,

re-entered our lives ten years ago when we resumed our friendship in Dubai. We

go back a long way, to the early days of the Nation

when Azhar had two legs to the present time when my old whisky-drinking mate

has had more marriages than most people have limbs.

Few journalists of our era are impressed by

today’s media. Somehow the 24-hour news cycle, often fed by an unfounded rumour

mill lacks the authenticity of our days hunting stories. And social media, with

its unsubstantiated anonymous attacks on individuals, is not a freedom to be

lauded.

Working on the Nation

had its frustrations, but any failures were always forgotten by the elation of

nailing a good exclusive splash and knowing that the by-line was well earned in

what was the golden age of journalism.

David

Barnet, Azhar Chaudry, Mike Parry at work covering the East African Safari,

once the highlight of the Nairobi Easter Weekend

Comments